BEIRUT — In any American university, what the six researchers in this room are doing would be totally unremarkable: launching a new project to use the tools of social science to solve urgent problems in their home countries.

But for the young Arab Council for the Social Sciences, this work is anything but routine. The group’s fall meeting, initially planned for Cairo, was canceled at the last minute when Egyptian state security agents demanded a list of participants and research questions. The group relocated its meeting to Beirut, meaning some researchers couldn’t come because of visa problems. Still others feared traveling to Lebanon during a week when the United States was considering air strikes against neighboring Syria. Ultimately, the team met in an out-of-the-way hotel, with one participant joining via Skype.

Their first, impromptu agenda item: whether any Arab country could host their future meetings without any political or security risk.

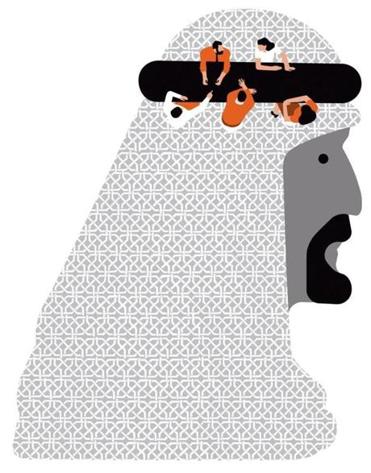

The council’s struggle reflects, in microcosm, a much bigger problem facing the Middle East. With old regimes overthrown or tottering, for the first time in generations a spirit of optimism about change has swept through the region. The Arab uprisings cracked open the door to new ideas for how a modern Arab nation should govern itself—how it could rebalance authority and freedom, religious tradition and civil rights. But a key source of those new ideas is almost completely shut off. With few exceptions, universities and think tanks have been yoked under tight state control for decades. Military and intelligence officials closely monitor research, fearing subversion from political scientists, historians, anthropologists, and other scholars whose work might challenge official narratives and government power.

Just one year after its launch, the ACSS is hoping to fill that vacuum, giving backing and support to scholars who want to do independent, even critical thinking on the problems their societies face. It’s a daunting order in a region where for generations talented scholars have routinely fled abroad, mostly to Europe and North America.

“There’s been almost a criminalization of research here,” says Seteney Shami, the Jordanian-born, American-trained anthropologist tapped to get the new council running. “We want to change the way people think about the region.”

It took nearly five years of planning, but the new council is now finishing its first year of operation. It has awarded roughly $500,000 to 50 researchers. Its goal is ambitious: to build an enduring network that will connect individual researchers who until now have mostly labored alone, under censorship, or overseas. The council aims to give those thinkers institutional punch—not just funding for projects that aren’t popular with local regimes or Western universities, but muscle to fight authorities who still maneuver to block even the most innocuous-sounding research missions. Today issues of ethnic, sectarian, and sexual identity are still taboo for governments—and they’re precisely the focus for most of the researchers who met in Beirut.

Shami and the other founders envision the council as only a first step, helping push for new openness in universities and in publishing. Ultimately, they believe, it stands to change not only how Arab countries are perceived abroad, but the way those countries are governed. Given the incredible turbulence in the Arab world today, it’s easy to see why a new flowering of social science is needed—and also why it’s a risky proposition for whoever hopes to set it in motion.

***

When we think about where ideas come from, we often picture lone thinkers toiling indefatigably until they achieve their “eureka” moments. But in fact, the ideas that change the way we organize or understand our daily world grow most readily from ecosystems that can train such scholars, test their claims, and ultimately spread and promote their new thinking. The modern West takes this system for granted; universities are perhaps the most important nodes in a network that also includes foundations, think tanks, and relatively hands-off government funding agencies.

Even societies like China, with its tradition of centralized state control, support a vigorous web of universities and institutes that produce and test ideas. In China, the government might drive the research agenda—rural educational outcomes, say, or international trade negotiations—but researchers are expected to produce rigorous results that stand up to outside scrutiny.

Not so in the Arab world. Despite a historic scholarly tradition, and a vigorous cohort of contemporary thinkers, the intellectual institutions in Arab countries are today almost universally subordinated to state control. As the dictators of the 1950s matured and grew stronger, they feared—correctly—that universities would nurture political dissent and that students were susceptible to free-thinking. (Even today, groups like the Muslim Brotherhood induct most of their leaders into politics through university student unions.) So they dispatched intelligence officers to control what professors taught, researched, and published, and to curtail student activism of a political flavor.

To the extent that think tanks, institutes, and journals were allowed to exist at all, they became either government mouthpieces or patronage sinecures. Plenty of individual scholars have continued to work in an independent vein, and many do research or publish work outside the influence of the ruling regime. For the most part, though, they do so abroad; those who speak openly in their home countries have often encountered gross repression, like the Egyptian sociologist Saad Eddin Ibrahim, an establishment thinker who was imprisoned in 2000 for taking foreign grant money. His prosecution—despite his close ties to the ruling dictator’s family— served as a reminder to other scholars not to stray too far from the state’s goals.

The obstacles to researchers who hope to confront the region’s problems run even deeper than that: in most Arab nations, even basic data on public issues like water consumption, childhood education, and women’s health are treated as state secrets. So are government budgets, and anything to do with the military, the police, and industry. Egypt still tightly guards access to land registries running as far back as the Ottoman Era; Lebanon famously hasn’t conducted a census since 1932, and refuses to release any government data about the population size or its religious composition. International agencies like the World Bank are allowed to conduct surveys and research as part of development aid projects, but only on the condition that they keep the data confidential.

As a result, great Arab capitals like Damascus, Beirut, Baghdad, and Cairo, once among the world’s great centers of learning, have suffered a systematic impoverishment of intellectual life, especially in the realms in which it is now most needed.

***

In many ways Seteney Shami’s career illuminates those challenges precisely. She left her native Jordan first for the American University of Beirut and then to earn an anthropology PhD from the University of California at Berkeley. Even as a young scholar, she knew she might face problems at home simply for writing about matters of identity among her own ethnic group, the minority Circassians, so she had her dissertation removed from public circulation. In the 1990s, she returned to the Middle East and built a well-regarded graduate program in anthropology at Jordan’s Yarmouk University—one of few rigorous graduate-level social sciences departments in the region. The experiment was short-lived, collapsing after only a few years when government patronage hires swamped the university faculty. Several scholars, including Shami, left.

She spent the next decade at US-funded foundations, working in Cairo for the Population Council and later in New York for the Social Science Research Council. She found that the scholars with whom she collaborated—and to whom she sometimes gave grants—relished the networks they built and the ideas that flowed when they had a chance to work with colleagues from different Arab countries, as well as in Europe and the United States. But there was a hitch: When the grant money ended, so did the network. In the West, such a change wouldn’t matter so much; the scholars would always have their home institutions to fall back on. Not so for a scholar in Jordan or Egypt, whose home institution might be far from supportive of his or her work.

“There is no institutional incentive to produce research in most Arab universities,” says Sari Hanafi, a sociologist at the American University of Beirut who is on the board of the new council. Hanafi conducted his own study of academic elites in the region, and discovered that most regional research was confined to safe descriptive projects—“production that will not question religious authority or the political system.” Essentially, it’s scholarship that doesn’t produce any new knowledge, or offer the possibility of change.

So a group of scholars including Shami and Hanafi began to conceive of something that would rectify the problem. Their vision isn’t a “think tank” in the Washington sense, but really almost a substitute for what universities do, creating a new and permanent forum to research, talk about, and solve serious social problems, outside government influence.

They secured funding from the Swedish government and later from Canada, the Carnegie Corporation, and the Ford Foundation. Among Arab countries, only Lebanon had laws that allowed a foreign international organization to operate free from government interference; even here, it took two full years for ACSS to clear all the red tape. In a way, the group’s timing was fortuitous: By the time the organization came online in 2011, with a few dozen scholars participating, the Arab uprisings were in full swing.

The first projects illustrate the flair ACSS is bringing to the sometimes stuffy world of social science. One study focuses on inequality, mobility, and development, and has brought together economists and other “hard” social scientists to explore issues like the impact of refugees from Syria’s civil war. A second, called “New Paradigms Factory,” unabashedly seeks to midwife the region’s next big ideas, asking scholars to challenge its dominant notions of sovereignty, national identity, and government power. The third major project, “Producing the Public in Arab Societies,” probes minority identity, community organizing, and alternative media sources—sensitive issues that governments steer away from, but that will be key to any new ordering of Arab civic life.

***

Some among the inaugural crop of researchers worry that despite its forward-looking visions, the window for an experiment like the Arab Council for the Social Sciences might already be closing. Two years ago, when Shami recruited her first team of scholars and grant recipients, a wave of optimism was washing over the Arab world. “It was a time to be brave, to test the boundaries of free expression,” she said.

Now, many of the same old restrictions have returned: Egyptian secret police, who had backed off after dictator Hosni Mubarak’s fall, resumed their open scrutiny of intellectuals after the military coup in July. Qatar, Bahrain, and the United Arab Emirates, fearing revolts from their own citizens, have also tightened their approach to academic inquiry, shutting down local research institutes and banning critical academics from attending conferences and teaching at international universities. Several of the scholars who met in Beirut as part of the “Producing the Public” working group declined to speak on the record even in general terms about the ACSS, fearing that any publicity at all might interfere with their work.

The first ACSS projects will take several years to yield results, and Shami says the long-term impact will depend, in part, on whether Arab governments continue to actively persecute intellectuals they perceive as critics. Meanwhile, Shami says, the group intends to go where it is most acutely needed—funding the edgiest and most relevant scholarship, and pushing for more open access to archives and data. To make up for the lack of regional peer-reviewed journals, it might begin publishing research itself. With the grandiose-sounding goal of transforming the entire discourse about the Arab world, Shami is aware that ACSS might fail; but she’s not interested, she said, “in biding our time and holding annual conferences.” If it proves necessary, she said, ACSS might create its own university.

Already, though, ACSS has had some visible impact. Omar Dahi, an economist at Hampshire College in Massachusetts, won a grant from the new council to study the way Syrian refugees are supporting themselves and how they are transforming the nations to which they’ve fled. He’s spending the semester in Beirut, and he expects to produce a series of articles that will bring rigor to a heated and topical policy debate. The council, he says, allows Arab scholars “to answer their own questions, and not only the questions being asked in North American and Western European academia.”

“It’s not easy, and ACSS alone is not going to be able to do it,” Dahi said. “But you have to start somewhere.”

Thanassis Cambanis, a fellow at The Century Foundation, is the author of “A Privilege to Die: Inside Hezbollah’s Legions and Their Endless War Against Israel.” He is an Ideas columnist and blogs at thanassiscambanis.com.